Leather

I. M. Godfrey

Introduction

The skin of any animal can be used to make leather. The physical characteristics of leather and its susceptibility to deterioration depend on the skin type and the processing treatment applied to it. Long before genuine tanning processes were employed to prepare leather, raw hides and skins were subjected to a variety of procedures designed both to preserve and alter their properties. Examples of these procedures include working oil, grease and even brain substance into raw skins, softening hides by chewing (Eskimo) and exposing skins to smoke (Waterer 1972).

Animal skin products have been used for domestic purposes from ancient times until the present. These materials were used over 4,500 years ago in the early civilisations of Egypt, Assyria and Babylonia (Reed 1972). About 3,500 years ago the Egyptians were making leather from the hides and skins of ox, calf, sheep, goat, lion, panther, gazelle, cheetah, antelope, leopard, camel and hippopotamus. Depending on the requirements of the final product, dehairing baths, alum tawing, vegetable and oil tannage, colouring and dyeing were all used. Leather products of this period included document rolls, sandals, aprons, shields, saddles, boats, balls and thongs for bindings (Reed 1972).

Of major archaeological and historic interest are leathers derived from the more common animals, such as those made from the hides of cows, sheep, goats, pigs and horses. Leathers can be differentiated by the characteristic hair follicle patterns on their grain surfaces. Preparation of leather from the skins of marine animals and reptiles is a more recent development.

Processing Hides and Skins

Skin products include rawhide, parchment, semi-tanned leather and fully tanned leather. The nature of skin and its conversion into leather are described extremely well by Waterer (1972). The following summarises much of Waterer’s descriptions.

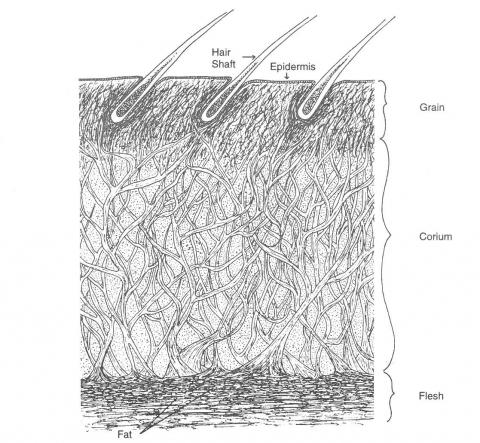

Skin is a complex structure made up of hair, a protein-containing layer of collagen fibre bundles, sweat glands, fat and blood vessels (Figure 1). The proteinaceous layer is a three-dimensional weave of collagen fibre bundles, large and loosely woven in the corium but fine and tightly packed in the protective, outer grain layer. Collagen molecules are made up of amino acids, linked by polypeptide bonds to form chains that combine in a helical fashion.

Figure 1: A cross-section of leather hide.

The processing of skins or hides may involve some or all of the following techniques:

- isolation of the corium (collagen layers);

- curing (dehydration by sun drying, dry or wet salting and pickling);

- tanning (vegetable, mineral or oil processing);

- dressing; and

- finishing.

During processing both the epidermal and the fatty layers of the skin are removed. Tanning processes are then used to stabilise the collagen fibre tissue. Details of some of these processes are outlined below.

Rawhide is the untanned skin of an animal which has had all of the flesh removed before drying. It is not leather, having not been exposed to any tanning processes. It is usually a very rigid, tough material, used where these properties are essential. Despite its inherent toughness, rawhide is in many ways the least durable of the skin products because of its susceptibility to deterioration and its moisture sensitivity. Some of its uses include the manufacture of suitcases, hammer heads, drum coverings, thonging and lashings.

Parchment is prepared by removing the flesh from the skin and drying the skin under tension by stretching it on a frame. It is usually light coloured, opaque and smooth and takes ink and colours well. Modern parchments are considered inferior in their properties to medieval or ancient parchments because of the different processing methods and materials employed (Reed 1972).

Semi-tanned leather (‘buckskin’ or ‘buff’ leather) is produced by stretching the skin and rubbing an oil and fat emulsion (sometimes from the brain of the animal) into it. The skin is manipulated until it is dry, soft and flexible. It is often smoked after this. When ‘new’, semi-tanned leather is soft, suede-like, extremely flexible and is considered to be quite durable. This oil ‘tanned’ leather is now most commonly encountered in the form of ‘chamois’ or ‘wash’ leather. In earlier times it was used for clothing, pouches, gloves, saddle seats, military uniforms and military equipment.

Fully tanned leather is the end product of the tanning and finishing of cured skins. Either vegetable or mineral tanning processes are used to raise the shrinkage temperature of leather, to prevent bacterial decay and in the case of chrome tanning, to impart water resistance to the leather. These processes involve complex chemical reactions between the tanning agents and the helical collagen molecules.

Vegetable tanning uses the tannins, found in the bark, wood, leaves and fruits of particular plants, to stabilise the collagen fibres. Before finishing the leather ranges in colour from pale to reddish brown, depending on the tanning agents used.

Mineral tanning refers to the use of metal salts to tan the leather. Salts that have been used include aluminium, chromium, zirconium and iron. Originally a solution of alum and salt (‘tawing’) was used to produce a white leather, which could then be dyed. Leather produced by tawing is not ‘true leather’ as the original raw skin can be regenerated by immersing it in warm water. Zirconium salts have been used to produce a washable white leather.

In the 1880s chrome salts were used to produce leathers which were hard-wearing, stable and water resistant. Chrome-tanned leather has a characteristic bluish colour that can be seen in the middle of a cross-section of the skin. Chrome-tanned leathers, which now make up about 90 % of the world’s leather production, cannot be embossed because of their resilience and open texture, making them unsuitable for bookbinding and other similar kinds of work.

Dressing leather involves incorporating materials such as fats and oils into it in order to lubricate the leather fibres and prevent sticking when dried. The amount and type of fat incorporated into leather and the mechanical treatment of skins are used at this stage to produce the desired properties. Sole leather, usually vegetable tanned for example, is rolled and only lightly oiled to produce a hard, slightly pliable material, whereas harness leather has a mixture of oil and tallow worked into it to induce strength, flexibility and water resistance.

Finishing processes tend to affect the appearance of the leather, with little impact on other properties (Figure 2). Traditional finishing processes include staining, dyeing, graining, plating, boarding, enamelling (to produce ‘patent’ leather) and abrading (to produce a suede or velvet finish).

Figure 2: Indian knife and scabbard that shows embossing, dyeing, and the corrosion of studs.

Today leathers are classified according to either the type of animal from which they were derived or the type of treatment to which they have been subjected. Smaller animals such as goats and sheep or the young of larger animals usually produce fine leathers.

Technically the term ‘leather’ only refers to skin products that have been fully tanned (vegetable or mineral tannages). The term will be used in this strict sense (unless specified otherwise) for the rest of this chapter.