Leather

I. M. Godfrey

Introduction

The skin of any animal can be used to make leather. The physical characteristics of leather and its susceptibility to deterioration depend on the skin type and the processing treatment applied to it. Long before genuine tanning processes were employed to prepare leather, raw hides and skins were subjected to a variety of procedures designed both to preserve and alter their properties. Examples of these procedures include working oil, grease and even brain substance into raw skins, softening hides by chewing (Eskimo) and exposing skins to smoke (Waterer 1972).

Animal skin products have been used for domestic purposes from ancient times until the present. These materials were used over 4,500 years ago in the early civilisations of Egypt, Assyria and Babylonia (Reed 1972). About 3,500 years ago the Egyptians were making leather from the hides and skins of ox, calf, sheep, goat, lion, panther, gazelle, cheetah, antelope, leopard, camel and hippopotamus. Depending on the requirements of the final product, dehairing baths, alum tawing, vegetable and oil tannage, colouring and dyeing were all used. Leather products of this period included document rolls, sandals, aprons, shields, saddles, boats, balls and thongs for bindings (Reed 1972).

Of major archaeological and historic interest are leathers derived from the more common animals, such as those made from the hides of cows, sheep, goats, pigs and horses. Leathers can be differentiated by the characteristic hair follicle patterns on their grain surfaces. Preparation of leather from the skins of marine animals and reptiles is a more recent development.

Processing Hides and Skins

Skin products include rawhide, parchment, semi-tanned leather and fully tanned leather. The nature of skin and its conversion into leather are described extremely well by Waterer (1972). The following summarises much of Waterer’s descriptions.

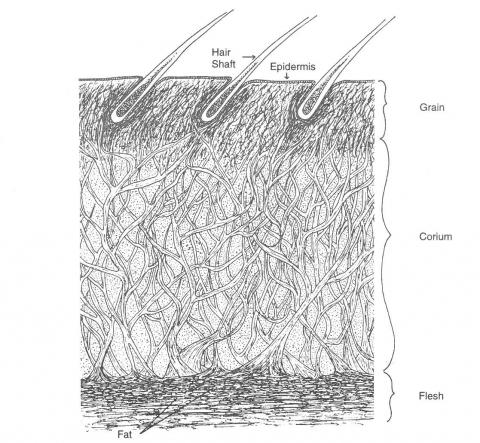

Skin is a complex structure made up of hair, a protein-containing layer of collagen fibre bundles, sweat glands, fat and blood vessels (Figure 1). The proteinaceous layer is a three-dimensional weave of collagen fibre bundles, large and loosely woven in the corium but fine and tightly packed in the protective, outer grain layer. Collagen molecules are made up of amino acids, linked by polypeptide bonds to form chains that combine in a helical fashion.

Figure 1: A cross-section of leather hide.

The processing of skins or hides may involve some or all of the following techniques:

- isolation of the corium (collagen layers);

- curing (dehydration by sun drying, dry or wet salting and pickling);

- tanning (vegetable, mineral or oil processing);

- dressing; and

- finishing.

During processing both the epidermal and the fatty layers of the skin are removed. Tanning processes are then used to stabilise the collagen fibre tissue. Details of some of these processes are outlined below.

Rawhide is the untanned skin of an animal which has had all of the flesh removed before drying. It is not leather, having not been exposed to any tanning processes. It is usually a very rigid, tough material, used where these properties are essential. Despite its inherent toughness, rawhide is in many ways the least durable of the skin products because of its susceptibility to deterioration and its moisture sensitivity. Some of its uses include the manufacture of suitcases, hammer heads, drum coverings, thonging and lashings.

Parchment is prepared by removing the flesh from the skin and drying the skin under tension by stretching it on a frame. It is usually light coloured, opaque and smooth and takes ink and colours well. Modern parchments are considered inferior in their properties to medieval or ancient parchments because of the different processing methods and materials employed (Reed 1972).

Semi-tanned leather (‘buckskin’ or ‘buff’ leather) is produced by stretching the skin and rubbing an oil and fat emulsion (sometimes from the brain of the animal) into it. The skin is manipulated until it is dry, soft and flexible. It is often smoked after this. When ‘new’, semi-tanned leather is soft, suede-like, extremely flexible and is considered to be quite durable. This oil ‘tanned’ leather is now most commonly encountered in the form of ‘chamois’ or ‘wash’ leather. In earlier times it was used for clothing, pouches, gloves, saddle seats, military uniforms and military equipment.

Fully tanned leather is the end product of the tanning and finishing of cured skins. Either vegetable or mineral tanning processes are used to raise the shrinkage temperature of leather, to prevent bacterial decay and in the case of chrome tanning, to impart water resistance to the leather. These processes involve complex chemical reactions between the tanning agents and the helical collagen molecules.

Vegetable tanning uses the tannins, found in the bark, wood, leaves and fruits of particular plants, to stabilise the collagen fibres. Before finishing the leather ranges in colour from pale to reddish brown, depending on the tanning agents used.

Mineral tanning refers to the use of metal salts to tan the leather. Salts that have been used include aluminium, chromium, zirconium and iron. Originally a solution of alum and salt (‘tawing’) was used to produce a white leather, which could then be dyed. Leather produced by tawing is not ‘true leather’ as the original raw skin can be regenerated by immersing it in warm water. Zirconium salts have been used to produce a washable white leather.

In the 1880s chrome salts were used to produce leathers which were hard-wearing, stable and water resistant. Chrome-tanned leather has a characteristic bluish colour that can be seen in the middle of a cross-section of the skin. Chrome-tanned leathers, which now make up about 90 % of the world’s leather production, cannot be embossed because of their resilience and open texture, making them unsuitable for bookbinding and other similar kinds of work.

Dressing leather involves incorporating materials such as fats and oils into it in order to lubricate the leather fibres and prevent sticking when dried. The amount and type of fat incorporated into leather and the mechanical treatment of skins are used at this stage to produce the desired properties. Sole leather, usually vegetable tanned for example, is rolled and only lightly oiled to produce a hard, slightly pliable material, whereas harness leather has a mixture of oil and tallow worked into it to induce strength, flexibility and water resistance.

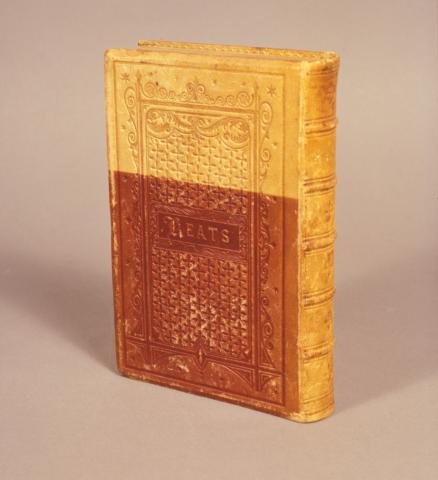

Finishing processes tend to affect the appearance of the leather, with little impact on other properties (Figure 2). Traditional finishing processes include staining, dyeing, graining, plating, boarding, enamelling (to produce ‘patent’ leather) and abrading (to produce a suede or velvet finish).

Figure 2: Indian knife and scabbard that shows embossing, dyeing, and the corrosion of studs.

Today leathers are classified according to either the type of animal from which they were derived or the type of treatment to which they have been subjected. Smaller animals such as goats and sheep or the young of larger animals usually produce fine leathers.

Technically the term ‘leather’ only refers to skin products that have been fully tanned (vegetable or mineral tannages). The term will be used in this strict sense (unless specified otherwise) for the rest of this chapter.

Deterioration

As mentioned in the introduction, leather is composed of tanned collagen, moisture, oils and fat. The amino acids that link to form collagen molecules give leather its slightly acidic nature, with a pH range between 3 and 6. The water and fat contents in leather should range between 12 - 20 % and 2 - 10 % respectively. Within these limits equilibrium and leather condition is maintained; outside them, deterioration accelerates. If there is too much fat in the leather for instance, water is repelled, resulting in the leather eventually becoming hard, brittle and inflexible. Once this occurs, it is often difficult to return the leather to its original condition.

Leather is affected adversely by a range of environmental and biological agents, careless handling and poor storage and display techniques. Chemical changes may take place in the tanning agents and other materials used in the manufacturing processes as well as in the collagen molecules. A comprehensive review of leather deterioration mechanisms is provided elsewhere (Kite and Thomson 2006). Some of these deterioration agents and processes include:

- attack by moulds, bacteria, rats, termites and many kinds of insects. A combination of excessive lubrication with oils and fats and high relative humidity (above 70 %) provides the right conditions for mould to develop on leather;

- drying out and the development of hard, brittle and cracked leather due to excessive lubrication and/or, low relative humidity (below 40 %) and/or moderate heat and relative humidity fluctuations;

- corrosion of metals in contact with fatty materials incorporated in leather dressings. For example, a turquoise, waxy substance often forms on copper fastenings attached to leather (Figure 3);

- attack on collagen molecules is catalysed by metal ions, copper (II), iron and cobalt ions in particular, and may lead to the breakdown of leather. These metals may have been incorporated in the leather from water and other materials used in tanning, from dyes, by direct contact with metals as a result of manufacturing processes or contact with metals in archaeological deposits;

- the effects of light, which include attack on the polymeric collagen components themselves, fading of dyes incorporated in leather (Figure 4) and interaction with atmospheric compounds to form harmful substances such as sulphur trioxide. Skin products that still have hair attached are susceptible to both insect attack and light-induced damage that may result in substantial hair loss;

- physical damage by too frequent or too vigorous cleaning, rough handling or storage of leather objects in conditions under which stresses and strains are induced in the object;

- the development of ‘red rot’ in vegetable tanned leather objects. Certain items of harness, military equipment, book bindings and upholstery are susceptible to this type of decay that is caused by atmospheric pollutants; and

- chemical and mechanical damage caused by dust. The sharp edges of minute dust and dirt particles are abrasive and can cause fibre damage if removed by methods other than suction. Dust also acts as a nucleation centre, attracting fungal spores and acting as a centre for condensation and subsequent chemical attack.

Figure 3: Corrosion of copper alloy studs due to excess fat in the leather. Turquoise waxy material is evidence of copper corrosion.

Figure 4: Leather bound book of Keats’ poems showing fading due to light exposure.

Preventive Conservation

Environment

Display and store items made from leather, hide and skin in a clean, well-ventilated environment maintained at a maximum temperature of 25 °C with a relative humidity in the 45 - 65 % range, with daily fluctuations limited to 4 °C and 5 % respectively.

Very dry conditions (less than 40 % relative humidity) will cause loss of moisture and embrittlement while high humidity (greater than 70 % relative humidity) encourages mould growth. Parchment is very sensitive to relative humidity fluctuations and changes dimensions as it absorbs and releases moisture into its surroundings.

Protecting skin products in a storage or display cabinet will help to stabilise environmental fluctuations while also providing protection against dust and insect attack.

As all light has the potential to damage leather, keep light levels to a minimum, particularly for dyed leather (see below for recommended levels). Avoid exposing any leather to bright spotlights or direct sunlight as both of these can cause discolouration, desiccation and embrittlement.

| Best light values for leather objects | ||

|---|---|---|

| Material | Total white light (lux) | Maximum UV (µWatts/m2) |

| Dyed leather | 50 | 1,500 |

| Undyed leather | 200 | 15,000 |

More information on aspects of preventive conservation is provided elsewhere (Raphael 1993, Kite and Thomson 2006).

Storage and Display

To maintain leather in good condition a high standard of cleanliness is needed. Vacuum and remove dust from storage areas regularly to minimise the likelihood of microbiological, insect or rodent attack.

Protect leather objects from dust (cupboards, unbleached calico or tyvek dust covers, acid-free boxes or acid-free tissue) and inspect them frequently, preferably every six months, to ensure mould or insect infestations are noted at an early stage. Use only unbuffered acid-free materials with leather because buffered acid-free materials are alkaline and are therefore potentially damaging to the slightly acidic leather.

Support leather objects in their desired shape when in storage and on display so that they do not need reshaping as they age and harden. Avoid sharp folds or creases in leather unless it is the original shape of the object. Fill rounded items with unbuffered, acid-free tissue paper. Supports of other shapes can be made from chemically stable polyethylene or polypropylene foams. To avoid stressing them, store large or long leather pieces horizontally.

If three-dimensional objects are unable to support their own weight, support them internally. The form of the support will depend on the shape of the object and the weight of leather to be supported. Fit leather clothing or large objects such as saddles on made-to-measure dummy mounts. Chemically stable materials, such as the above-mentioned foams, linen, dacron and most metals, may be used in the manufacture of these supports.

Use painted metal storage cupboards and furniture to reduce the risk of acidic vapours from wood products coming into contact with skin materials. If wooden furniture is used then seal and line it with impermeable coatings (for example, clear, water-based polyurethane) or laminates (see the chapter Preventive Conservation: Agents of Decay).

Standard conservation-quality mounting and framing is usually adequate to protect art or documents on parchment.

Treatments

If leather objects are stored and displayed in good conditions, the need for potentially damaging treatments can be reduced or avoided. Do not attempt treatments that involve the use of detergents, stain removers and similar chemicals before consulting a conservator to obtain the most up to date advice. Any treatment should be the least interventive possible.

Cleaning Leather

Cleaning has the potential to damage leather and should not be considered an automatic option for leather objects. There are some situations, however, when cleaning is recommended. These include:

- objects that have been acquired recently. Before their addition to the collection such objects should be inspected and cleaned if necessary. Inspect the objects to reduce the risk of contaminating the rest of the collection; and

- objects on display or in storage that are at risk due to damaging surface contaminants.

Before cleaning any leather a number of factors should be considered. These include:

- the type of leather;

- the type of surface;

- the nature of any contaminants; and

- what is to be cleaned.

The last point needs to be considered carefully as dirt or other accretions accumulated during an object’s historical usage must be viewed in a different light to that which has been deposited during its period in storage. If an object is in a fragile condition it may be better not to clean it to avoid further damage. Instead, try to protect the object against further soiling.

Surface deposits that may need to be removed by cleaning include:

- inorganic dirt, dust and salts;

- organic residues such as fatty or gummy spews; and

- mould.

To distinguish mould, spews and crystalline salts examine the leather surface under a microscope. The crystalline nature of salts would be clearly evident and the presence of fungal hyphae (fine fibrous strands) should allow these contaminants to be identified. Gummy spews are formed by the breakdown of oils and fish oils in particular. These resinous-looking substances are usually smelly and unpleasant to touch and handle. Fatty spews are greasy deposits that appear on the leather surface and are sometimes mistaken for mould. They form when solid fats, or their breakdown products, migrate to the surface. Lubricants used to soften leather are often the source of these fatty materials.

Cleaning Techniques

If cleaning is necessary then the following mechanical and wet cleaning approaches may be considered:

- vacuum cleaning;

- brushing with a soft brush;

- compressed air;

- granular erasers;

- scraping with a wooden spatula;

- petroleum-based solvents such as white spirit and hexane; and

- water-based cleaning - including the use of pure water, alcohol and water solutions, and emulsion cleaners.

Never wet the leather surface during cleaning as this increases the likelihood of the leather hardening when it dries. An additional risk associated with water-based cleaners is darkening of the leather surface. Avoid water-based cleaning methods unless the leather surface is relatively impervious to water.

Vacuum cleaning, with the nozzle just above the leather surface, is probably the safest cleaning method. It is particularly suited to cleaning dusty leather in good condition. Place a gauze screen on the end of the nozzle when cleaning. Check this periodically to make sure that pieces of the surface are not being removed.

Brushing with a soft squirrel hair or camel hair brush may also be used to remove surface dust. Note that even using a soft-bristled brush may not prevent damage to fragile objects as dust is abrasive and pieces may be dislodged.

A gentle stream of compressed air may be appropriate for some objects. To prevent re-deposition of dust, carry out this procedure either in the open air or in a fume cupboard. As with brushing, there is a danger of dislodging fragile pieces.

Approved granular erasers, such as Artgum 211 or Faber Castell and sponges of the Wishab type, may be used to remove more stubborn dirt, but only on surfaces in good condition. Erasers should not contain sulphur or chlorine compounds. Their use is outlined below:

- use a household grater to finely grate an eraser. A plastic grater is preferred as the metal variety may rust or shed small metal particles;

- spread the grains over the leather and lightly rotate them with the palm of the hand or the flat of the fingers until the entire area has been covered; and

- remove the eraser crumbs with a vacuum cleaner. This is extremely important as the residues may affect the texture, colour, pH and ‘wettability’ of the leather. In addition, as the crumbs age they harden and may cause physical damage to the leather.

Scraping, using a soft wooden spatula, may be used to remove thick surface deposits such as those occasionally formed by fatty spews. Only use this method to remove the bulk of the deposit and take particular care not to damage the leather surface. Solvents may be used to remove the residues left after scraping (see below).

Use a sponge, moistened slightly with water, to remove water-soluble dirt from leather objects that are in good condition and whose surface is protected by a water-resistant coating (wax, resin or similar). Identify the nature of the coating before carrying out this type of cleaning.

Use petroleum-based solvents such as white spirit or hexane, applied either as a poultice or with a sponge, to remove thin films of fatty or gummy spews. Test the solvents on an inconspicuous area of the object to ensure that surface finishes are not affected.

Use alcohol or alcohol/water solutions (50/50 mix) to remove surface salts. A low water content is desirable to minimise potential damage to the leather. Test the solution before use to ensure it has no detrimental effect on the leather surface.

An emulsion cleaner, whose ingredients and method of use are described below, is based on a formulation described in Fogle (1985). It has been used successfully to remove stubborn inorganic and organic dirt. As this formulation contains some water, test it before using it on a large scale.

| Non-ionic detergent (for example, Teric N9, Arkopal N090) | 20 ml |

| Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) | 2 g |

| Distilled water | 1 L |

| X-4 solvent (hexane) | 2 L |

Prepare the cleaner in the following manner:

- vigorously mix the detergent, CMC and distilled water for several minutes;

- leave the mixture to stand overnight. This gives the CMC time to swell; and

- add 150 ml of this solution to 1000 ml of X-4 solvent and shake vigorously until a creamy emulsion is formed.

The cleaning solution keeps indefinitely but should be shaken before use. Before using the cleaner, test it on an inconspicuous area of the object to be cleaned to ensure it has no significant effect on either surface coatings or on the leather itself. Rub the cleaner onto the surface with a clean cloth, rotating the cloth as it becomes soiled. If the object is very small or delicate, use cotton buds (or similar) to apply the cleaner.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that although saddle soap appears to have little detrimental effect on leather objects still in use, museum objects cleaned with this soap often seem to be in worse condition than untreated objects. Of major concern is the alkaline nature of the saddle soaps and the effect they and similar products can have on the leather (which is naturally acidic). Its use is not recommended for objects in storage or on display.

Biological Infestation - Mould and Insects

Avoid using chemical reagents to treat biological infestations as there is the risk of damage or contamination of treated objects. Methyl bromide, a commonly used fumigant, is particularly damaging to leather and should not be used. Non-toxic methods of treatment are available, with freezing and oxygen depletion approaches described earlier (see the chapter, Mould and Insect Attack in Collections). To be sure that the safest method is being employed to treat an object, contact a conservator before any treatment.

Mould

Aim to prevent mould growth by ensuring there is effective air circulation in storage areas, that relative humidity is kept below 70 % and over-lubrication is avoided.

Insects

Insects, including carpet beetles, spider beetles and cockroaches, will attack leather. Damage also may occur as a result of other insect types burrowing through leather in search of suitable foods such as the animal glue used in leather bindings or the wooden supports of upholstered furniture.

Preventing insect attack is preferable to treatment. Steps to minimise the risk of insect attack have been outlined earlier (see the chapter Mould and Insect Attack in Collections).

Lubrication and Dressing of Leather

Lubrication is probably not necessary for most objects in a collection as this process is often accompanied by unwanted side-effects such as increasing acidity, discoloration, the formation of surface spews and damage to surface finishes. Dressings should therefore never be applied as a routine treatment. Take the following points into account before applying any lubricants to leather:

- for leather in storage, the main purpose of oils used in dressings is to prevent the leather from hardening if the relative humidity levels fluctuate widely. Environmental control of conditions is preferred to the application of dressings;

- the application of too much oil causes leather to repel moisture, a process that eventually produces a hard and brittle leather;

- too much applied oil stains the surroundings and attracts dust and insects;

- excess lubricant encourages mould formation;

- some dressings darken leather and lead to increased stickiness;

- dressings do not provide protection against acidic pollutants;

- if reshaping alone is required then often humidification alone will suffice (see below);

- dressings should not be used to ‘feed’ leather or to improve their appearance. If an improved appearance is desired and the object originally had a polished surface, apply a wax polish;

- never apply lubricants to objects containing untanned or semi-tanned materials or to either surface of painted or gilt leather; and

- lubrication of the leather covers of books is not recommended as the materials incorporated in the dressings make gluing repairs more difficult. There is also a tendency for these materials to migrate into the paper.

Note that as leathers age their ability to absorb fats and oils is reduced. The amount of fat and oil needed in archaeological and historic leathers (3 - 5 %) is less than in their modern counterparts (10 - 12 %). Pumping more lubricants into aged leather will only cause more problems.

To summarise, lubrication of leather is only necessary if:

- flexibility needs to be restored to an object;

- the storage or display environment fluctuates greatly, usually leading to an extremely dry or cracked object (due to shrinkage); and

- humidification alone is insufficient to induce enough flexibility for reshaping.

As most objects in collections rarely need to be flexible and hopefully will be stored in their desired shape and in relatively stable conditions, there should be little need for lubrication.

If flexibility must be restored to hardened leather, or the object is to be reshaped, re-humidify or ‘condition’ the leather before lubrication. Various procedures have been described that raise the humidity without wetting the leather (Calnan 1984, Kite and Thomson 2006). Two of these procedures are:

- covering flat leather with a layer of soft cotton fabric or spun-bonded polyester fabric like Reemay and then covering the cotton or polyester with either damp sawdust or damp blotting paper (overnight); or

- placing the leather in a humidity chamber.

Of these options, use of a humidity chamber is the preferred method (see ‘Humidification’ below for further details).

The lubricants, fats or oils, can then be added to leather using either a water-based emulsion or an organic solvent as the transport medium. Vegetable oils are not used as frequently as fats because in the long term they are more prone to oxidation, a process accompanied by yellowing and hardening of the oil and subsequent loss of lubricating properties. Always test lubricants on an inconspicuous area before large-scale use and apply them to the grain surface (to minimise the risk of tide marks forming on this surface).

Applying oils in emulsion (water-based) form increases the likelihood of oils remaining evenly distributed throughout the interior of the leather. An emulsion is the best vehicle for carrying the lubricant if tests show that:

- water does not discolour the surface; and

- the surface is permeable to water.

An emulsion formulation and method of application, as recommended in Fogle (1985), are described below:

| lanolin | 2 g |

| neats-foot oil | 10 g |

| non-ionic-detergent (Teric N9, Arkopal N090) | 6 g |

| distilled water | 100 ml |

The emulsion is prepared by:

- warming together (at about 60 °C) the lanolin and the neats-foot oil until they melt;

- cooling the mixture to 20 °C and then adding the detergent. Stir the mixture thoroughly and rapidly;

- slowly adding the distilled water (in small amounts) while stirring continuously; and

- observing the mixture for 10 minutes in a glass cylinder to see if it separates or remains as a stable homogeneous liquid.

This mixture contains no preservatives and is best used soon after being prepared. Refrigeration will extend its life for a few months. Paint the emulsion on the leather using a soft-bristled brush. If more than one coat is needed to achieve the desired flexibility, allow the leather to dry before applying the next coat.

Use an organic solvent-based dressing if the leather is:

- fragile;

- darkened by water; or

- impermeable to an emulsion due to the presence of a wax or other coating.

As for the emulsion, a formulation and method of application of a solvent-based dressing are described in Fogle (1985).

| lanolin | 2 g |

| neats-foot oil | 8 g |

| Shellsol T (aromatics-free White Spirit) | 100 ml |

Prepare the dressing by dissolving the lanolin and neats-foot oil in the Shellsol T. Apply the dressing by painting the solution on the leather using a soft-bristled brush. Allow the leather to dry between coats if more than one coat is needed to induce the desired amount of flexibility.

Some commercial neats-foot oil products contain significant quantities of impurities, triglycerides in particular. Solid triglycerides will settle out on the surface of leather after dressing to form fatty spews. To remove these from neats-foot oil, refrigerate it and discard the solid upper layer. If possible purchase ‘cold tested’ neats-foot oil which has already had the triglycerides removed.

If there is a surface finish that is impermeable to solvents it will resist penetration of oils and fats into the leather. In this situation it is better to rub an oil emulsion into the flesh side to encourage penetration. Care must be taken however to avoid tide marks on the grain surface.

A preparation such as British Museum Leather Dressing may be used to restore surface oil content if:

- dryness is only a surface condition; and

- the leather is very thin (for example, book covers, car seats).

This dressing, which should be applied sparingly, may be used with leather which incorporates metals. The beeswax in the composition leaves behind a thin film which will take a polish. A formulation is given below:

| lanolin | 200 g |

| cedar oil | 30 ml |

| beeswax | 15 g |

| X-4 solvent (or hexane) | 330 ml |

Prepare and apply the dressing as follows:

- mix the lanolin, cedar oil and beeswax together and melt by careful heating;

- rapidly pour the molten mixture into the cold X-4 solvent and allow it to cool with stirring;

- apply the dressing sparingly and rub it well into the leather with clean swabs; and

- polish the leather with a soft cloth two days after applying the wax.

Note that a careful assessment should be made before any treatment is applied to the leather of a book cover. In most cases it is preferable to store books under the best possible conditions (see the chapter, Paper and Books).

For more information on the lubrication and dressing of leather refer to publications by Calnan (1984), Fogle (1985), Tuck (1983) and Kite and Thomson (2006).

Humidification

Humidification can be used to condition and reshape leather.

A simple humidity chamber can be prepared using polyethylene sheeting and tape. Place the object to be humidified in the polyethylene ‘tent’ then increase the relative humidity using either an ultrasonic humidifier, a bowl filled with wet cotton wool or a jar containing water (50 %) and alcohol (50 %, methylated spirits or ethanol). Seal the tent with tape. The alcohol inhibits the formation of mould in the high relative humidity environment created inside the tent. Monitor the set-up to prevent condensation formation.

Usually conditioning is carried out overnight whereas the time for reshaping varies considerably between objects. The time taken for softening to occur depends primarily on the leather thickness and the presence or otherwise of surface coatings.

As the leather softens it is able to be reshaped slowly. Remove the object from the chamber periodically and progressively ease it into the required shape. Usually it is necessary to use padding during this process to maintain the gradually changing shape. Non-buffered, acid-free tissue or polyethylene foam are suitable padding materials.

Treatment of Attached Metal Fittings

Iron and copper alloys are commonly found as components of leather objects. Fats present in leather enhance the corrosion of these materials. A turquoise-blue, waxy material which forms on copper fittings is usually the most visible sign of corrosion.

Due to the intimate contact between the metals and the leather, immersion in chemical baths is usually not an option for the removal of disfiguring corrosion products. Careful application of physical methods is recommended. In some instances treatment chemicals may be applied using bentonite paste (see the chapter, Metals).

Copper corrosion products may be treated in the following way:

- use a soft wooden spatula to remove the bulk of corrosion products;

- use cotton buds soaked in leather cleaner (see earlier) to remove any residues; and

- coat the fittings with either microcrystalline wax or renaissance wax to minimise further corrosion. A corrosion inhibitor, benzotriazole (5 %), may be incorporated in the wax if additional protection is required.

Gentle, carefully applied abrasive methods are best to remove surface rust. Apply microcrystalline wax to the cleaned surfaces to protect against further corrosion.

Repair

The repair of tears and splits, infilling and consolidation of leather are highly specialised tasks. Advice from a conservator is strongly recommended.

Use a backing material to support any damaged areas. Materials that have been used include leather and woven and non-woven fabrics such as linen, Reemay and Cerex. Synthetic fabrics often are preferred for reinforcing fragile leather due to their dimensional stability, light weight and strength. Internally plasticised polyvinyl acetate (PVA), ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) emulsions or acrylic emulsions are suitable for bonding backing material to the flesh side (where accessible) of the damaged object.

Solvent-based adhesives are safest to use on moisture-sensitive materials made from rawhide and buckskin.

As well as case studies, examples of materials and techniques used for repairs, infilling and consolidation are provided elsewhere (Calnan, 1991, Kite and Thomson 2006).

Summary

- If possible, identify the leather or types of leather used.

- Check for mould or insect attack and treat before adding leather objects to other collection items.

- Maintain the temperature at 25 °C or below and the relative humidity in the range 45 - 65 % with daily fluctuations limited to 4 °C and 5 % respectively.

- Control light levels to below 50 Lux and 1500 µW/m2 (30 µW/Lumen) for dyed leather and below 200 lux and 15,000 µW/m2 (75 µW/Lumen) for undyed leather.

- Do not fold or crease flat leather objects.

- Support shaped objects with inert foam material such as polyethylene, polypropylene or dacron.

- Store in acid-free boxes or use textile covers. These protect from dust and act as a buffer against changes in relative humidity.

- Consult a conservator if specific treatments are necessary.

Bibliography

Calnan, C., 1984, The conservation of social history and industrial leather, in Taken Into Care: The Conservation of Social and Industrial History Items, Proceedings of the Joint UKIC/AMSSEE meeting, United Kingdom Institute of Conservation, London.

Calnan, C., (Ed.), 1991, Conservation of Leather in Transport Collections, papers given at a UKIC conference, Restoration ‘91, United Kingdom Institute of Conservation, London.

Dignard, C. and Mason, J., last modified: 2016-12-09, Caring for leather, skin and fur, Government of Canada, http://canada.pch.gc.ca/eng/1468243997245

Fogle, S., (Ed.), 1985, Recent Advances in Leather Conservation, The Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, Washington D.C.

Kite, M. and Thomson, R., 2006, Conservation of Leather and Related Materials, Elsevier, Oxford.

Raphael, T.J., 1993, The care of leather and skin products: a curatorial guide, Leather Conservation News, vol. 9, pp. 1-15.

Reed, R., 1972, Ancient Skins, Parchments and Leathers, Seminar Press, London and New York.

Tuck, D.H., 1983, Oils and Lubricants Used on Leather, The Leather Conservation Centre, Northampton.

Waterer, J.W., 1972, A Guide to the Conservation and Restoration of Objects Made Wholly or in Part of Leather, G. Bell & Sons, London.