Ethnographic Material

C. Corvaia, D. Gilroy and C. Harley

Introduction

Because they can be constructed from almost any type or mixture of materials, the care of ethnographic objects, probably more than any other type of collective material, presents a tremendous challenge to conservators and collectors alike (Figure 1).

It is worth listing some of these materials to highlight the high degree of care and sensitivity needed in handling, documenting and treating these artefacts. Materials used in ethnographic objects may include textiles, metals, plant material, stone, ceramics, skins, leather, furs, glass, feathers, shells, ochres, pigments and ivory, coupled with dyes, resins, oils, paints, blood and so on. Each of these material types can be further subdivided to give an even more imposing list of possible components which make up the class of collectables known as ethnographic objects. Plant material, for instance, can include wood, gourds, bark, paper, linen, cloth, reeds, leaves and vines.

Figure 1: This parang shows the range of material types that can be found within one object.

Note that some traditional societies have introduced modern materials into their objects. A background knowledge of the recent history of an artefact is therefore pertinent. It is also very important to understand the social and cultural backgrounds associated with objects so that no offence is caused, for example, by having a particular object on display.

In order to preserve ethnographic material it is essential to identify both the material components and the agents of deterioration.

Deterioration and Handling

Deterioration

Because of their complex nature many ethnographic objects are extremely susceptible to damage from the usual agents of decay (relative humidity, light, temperature, pollutants, dust, insects and poor handling).

As materials such as wood, leather, furs, paper and animal sinew react at different rates to changes in relative humidity, stresses will develop in composite objects if they are exposed to rapid changes in these conditions. Painted or pigmented surfaces for example, may become detached or powdery due to changes in either relative humidity or extremes of temperature.

Potential damage to the patina of metals, to low-fired clays, problems of salt incorporation in objects recovered from buried or wet sites and the effects of high temperatures on resins and waxes all complicate the already difficult situation of caring for these material types.

Objects that are moved from one climatic zone to another need special attention. Cellulose-based materials moved from the tropics to more temperate regions for example, should be slowly acclimatised to their new environment if drying stresses are to be avoided. Suitable storage and display environments, handling and acclimatisation of sensitive materials are described elsewhere (see the chapter Handling, Packing and Storage).

Documentation and Handling

Always wear cotton or rubber gloves when handling ethnographic objects. As many ethnographic objects have been treated with toxic chemicals, this will protect both the artefact and the handler.

Thoroughly examine the object and make notes on its condition, history (if known), the materials from which it is composed and the presence of any previous repairs or alterations. Record all components even if positive identification of the material type is not possible (for example, a specific resin type). Photographs and sketches are extremely important components of the overall documentation.

As these objects are often susceptible to insect infestation and fungal attack it is wise to have an inspection area away from any other objects that may be affected by cross-contamination.

Note that as some materials may be poisonous by intent, arrow tips or material in gourds for example, take great care during the examination process.

Good handling, storage and display practices are essential if ethnographic objects are to be appropriately cared for. Choose conditions and practices that are best for the most sensitive component of a composite object. As the range of ethnographic materials is too diverse to cover in this book, the following section on bark paintings has been included to illustrate a general approach to the care of ethnographic material

Bark Paintings

Introduction

Bark paintings produced by Australian Aborigines are usually made from sections of the outer bark cut from eucalyptus trees. The bark is heated and weighted to produce a flat surface, scraped and then sometimes treated with natural resins before being painted.

Traditionally natural ochres, clays, minerals and charcoal were used for pigments. These were sometimes mixed with natural binders such as plant gums or blood. More recently PVA emulsion has been used to bind pigments. For the past 40 years, commercial acrylic paints have also been used.

Deterioration

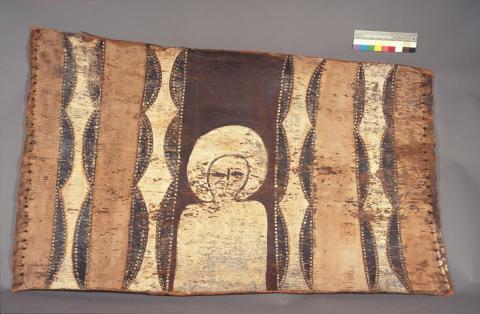

Most conservation problems associated with bark paintings are associated with relative humidity. High relative humidity levels encourage mould and fungal attack on binders and can cause bark fibres to relax and return to their original curved form (Figure 2). Some of the traditional pigments, clays in particular, are able to absorb moisture from the air. This may eventually cause them to break up by flaking, blistering or cracking.

In addition, fluctuations in relative humidity cause bark to expand and contract, usually across the grain. Pigments, because of their different composition, generally react to fluctuations in relative humidity to a lesser degree than the bark. This causes tension at the pigment-bark interface which if left unchecked will cause the two to separate.

Initially, pigmented areas crack, then ‘tent’ and finally spall off. White pigment, perhaps due to its relatively coarser grain, appears to be more sensitive than other colours. Problems with changes in relative humidity are common due to the fact that many bark paintings may be produced in a humid area but end up in a drier region. Low humidity can cause shrinking in bark fibres and splitting and flaking of paint.

Physical damage may also be caused by insect attack of the bark itself.

Figure 2: Aboriginal bark painting. Ochre paint is flaking due to bark curling.

Preventive Conservation

Store and display bark paintings at relative humidity levels of 45 – 55 % with a maximum fluctuation of 5 % in any 24 hour period. A stable environment is most important as twisting and warping may occur otherwise. Maintain temperatures in the range 15 – 25 °C with a maximum variation of 4 °C in any 24 hour period.

To prevent dust accumulation, store bark paintings flat and covered with acid-free tissue or in archival quality cardboard boxes. Support any curved areas with dacron or polystyrene beads in washed cotton or linen (Figure 3). Keep the storage area clean.

Figure 3: Decorated bark from New Britain. A cloth mask needs support before going into storage.

To minimise fading of dyes and natural pigments, maintain light levels at a maximum illuminance of 50 lux with minimal UV radiation (less than 30 µwatts/lumen).

As bark paintings respond to changes in their environment they will be damaged if they are attached to rigid supports which restrict these responses. It is important to allow the painting some flexibility. Recently, fibreglass backings have been applied to some bark paintings with foam inserts which permit movement. Unfortunately, the fibreglass backing technique is time consuming, involves the use of toxic chemicals and is very expensive. More practical methods using aluminium strips and polyethylene foam have been developed (Coote 1995). As the backing procedure is highly specialised, consult a qualified conservator for advice.

Inspect paintings regularly to guard against insect attack.

Treatments

While some details are given below of ways in which bark paintings can be treated, this work should be left to conservation professionals. Seek advice from a conservator rather than attempt to carry out work yourself.

Cleaning

Cleaning bark paintings which contain traditional pigments may be difficult because these pigments often become powdery as they age.

If consolidation of the pigments is needed, and dust is found on the painting, remove the dust to prevent staining of the pigment during consolidation. Use a very soft brush, preferably sable, with a very light action. Due to the sensitivity required, ask a conservator to carry out this work.

Although it is possible to clean acrylic painted areas in good condition with cotton swabs that have been slightly moistened with water, avoid using water and organic solvents to clean bark paintings. If moistened cotton swabs are used, do not contact the bark and dry the cleaned areas immediately. Use dry cotton swabs or something similar for this latter task.

Consolidation

Traditional pigments used in bark paintings often require consolidation. The main risk associated with consolidation is staining or darkening of the pigments by the consolidant. As results vary from painting to painting, test a range of possible consolidants before commencing full-scale treatment. Consolidation is a specialist task, requiring the skills of a conservator.

Although cellulose-based consolidants have less cohesive and adhesive strength than their synthetic counterparts, their use is generally recommended. Synthetic resins are not in keeping with the natural materials used in bark paintings and may produce a surface which is both glossy and prone to yellowing.

Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC, 5 g in 100 ml of water) is a widely used consolidant that rarely stains pigments. As CMC may affect any water-soluble pigments present in a painting, test it before application.

If flakes are lifting, introduce a consolidant beneath the flakes, with the flakes then gently laid down with the aid of silicon-release paper and weights.

Powdery areas may require application of the consolidant over the pigment surface. Do this by wetting out the pigment with ethanol (after testing for staining) and then manually applying the consolidant. The ethanol helps to draw the consolidant into the pigment and in some cases helps to reduce staining.

Occasionally, consolidants are sprayed over the bark surface. Although time-efficient, this procedure may not provide the thoroughness or penetration of consolidant that is achieved by working manually.

Other adhesives, which can be used include ethulose, potato starch, Klucel G and Klucel EF. Although the Klucel products (cellulose ethers) do not give a particularly strong bond, they have the advantage of being soluble in ethanol. Klucel EF is especially useful as it has a lower molecular weight than Klucel G and a more concentrated solution can be achieved without the viscosity which makes application difficult.

Note that cellulose-based consolidants are prone to mould attack. Display and store paintings treated with these materials in a stable environment with a relative humidity in the range of 45 – 55 %.

Insect Attack

Consult a conservation specialist if insect attack is a problem.

Oxygen deprivation is the most appropriate technique for insect control in bark paintings. Details of this technique are provided elsewhere (see the chapter Mould and Insect Attack in Collections). This approach is the least likely to damage the pigments.

Chemical fumigants and freezing techniques are not recommended as both will have deleterious effects on pigments in bark paintings.

Summary

- Identify all materials within the object.

- Obtain as much background detail or history before starting any treatments.

- Handle only with cotton or rubber gloves.

- Maintain temperatures and relative humidity levels in the ranges 15 -25 °C and 40 – 60 % with maximum variations of 4 °C and 5 % respectively in any 24 hour period or at levels suitable for the most sensitive material of a composite object (see the chapter Preventive Conservation: Agents of Decay.)

- Avoid direct sunlight and control display lighting.

- Consult a conservator before treating ethnographic materials.

Bibliography

Coote, K., (1995), Mounting Aboriginal bark paintings, SSCR Journal, vol. 6, pp. 7-9.

Horton-James, D., Walston, S. and Zounis, S., 1991, Evaluation of the stability, appearance and performance of resins for the adhesion of flaking paint on ethnographic objects, Studies in Conservation, vol. 36, pp. 203-221.

Léculier, A., 2000, Recommendations for Storage of Aboriginal Bark Paintings: A Technical Note, Studies in Conservation, vol. 25, pp. 37-40.

Rose, C.L., 1992, Preserving Ethnographic Objects, in K. Bachmann (Ed.), Conservation Concerns: A Guide for Collectors and Curators, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London, pp. 115-122.

Tsuneyuki Morita, T. and Pearson, C. (Eds), 1988, The Museum conservation of ethnographic objects, 9th International Ethnological Symposium, 1985, National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka, 290 pp.