Paintings

D. Gilroy, I. M. Godfrey and I. Loo

Introduction

Ancient cave and rock paintings provide evidence of the lifestyles and relationships between prehistoric people and their environments. These earliest of works, as with modern paintings, vary greatly in their subject matter, style, techniques and use of materials.

Paintings most often conjure images of framed pictures using oils, watercolours or acrylic on canvas, paper or wood panels. While watercolours will be referred to occasionally in this chapter, as much of the conservation focus for watercolours relates to the paper support, readers are directed to the Paper and Books chapter for further information about the care of these materials. The care and conservation of frescos and murals is also not covered in this chapter. The term ‘paintings’, for the purpose of this chapter therefore, will refer primarily to works on canvas, wooden panel and boards with media ranging from oils and egg tempera to synthetics. There are of course, a great many types of supports as well as finishes and materials. If we consider some of these materials it is obvious that the traditional term needs to be viewed in a broader context. Inks, chalks, acrylics, pastels, charcoal and other materials, either alone or in combination, together with a variety of grounds or varnishes may all be applied to a variety of supports. The addition of other materials, as in collage or ethnographic material, further blurs the boundary between painting and object.

Structure

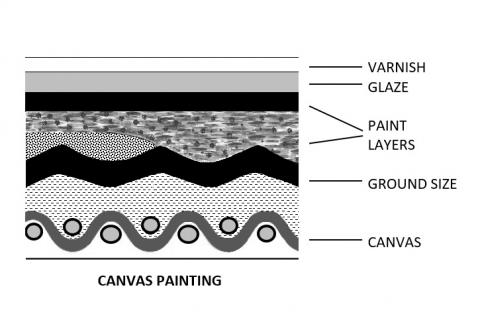

Paintings (easel paintings in particular), usually comprise the following elements (Figure 1):

- a support, predominantly a textile canvas, but may be composed of other materials such as wood, metal, ivory, bone, leather, glass or stone;

- an auxiliary support such a stretcher or a strainer to keep the painting taut. Keys, usually flat triangular wooden or plastic wedges, are used in the corners to adjust the tension of the fabric and to maintain a smooth appearance;

- a size, such as animal glue, is used on a canvas to fill pores, isolate coatings or to make surfaces suitable to receive coatings (Mayer 1991);

- a ground, such as gesso or pigments mixed with oil, usually to produce a white background, uniform texture, degree of absorbency, as well as an intermediate structural layer between the support and acidic painting layers;

- a paint layer composed of pigments (either organic or inorganic) and binders such as oils, egg tempera, gums, wax, or synthetic polymers and resins; and

- a varnish layer, applied to the surface of an artwork that may be either a natural resin like dammar, mastic or shellac or a synthetic resin such as alkyds, acrylics or ketones. Many acrylic paintings are not varnished.

Figure 1: A cross-section showing the structure of an easel painting.

Added to the above could be other material such as feathers, sand and wood, all of which react differently to the agents of deterioration.

Deterioration

Paintings are composite structures and there are complex interactions between the different components. Deterioration in paintings can stem from:

- poor artistic technique and material selection;

- chemical changes with time (natural ageing);

- changes due to external environmental conditions; and

- mechanical fatigue and physical damage.

Of these, poor artistic technique and material selection may be unavoidable and can contribute to a range of problems, particularly if successive paint layers were applied before the underlying layers dried sufficiently. In addition to problems associated with this ‘inherent vice’ of a painting, deterioration factors that most severely affect paintings include:

- temperature and relative humidity;

- light;

- pollution, including dust;

- biological deterioration; and

- physical effects including vibration, impact and poor handling

Fluctuations in temperature and relative humidity can cause painted canvas or wooden panels to expand under humid conditions and contract under dry conditions. These fluctuations may disrupt the bond between the paint layer and the support, leading to flaking and/or cracking paint, layer sagging or stretching of the support, desiccation and splitting, distortion or warping of the wooden elements and even mould growth under high relative humidity conditions. High relative humidity may also account for a chemical change from azurite pigments (blue) to malachite (green) compounds and the development of ‘blooms’ (a bluish-white haze) in varnishes, both of which affect the aesthetics of a painting. Exposure to elevated temperatures will accelerate chemical deterioration and may also cause paint binders to soften or break down.

Over-exposure to light is a major cause of deterioration for displayed artworks. Light can cause bleaching and fading of colours, particularly those derived from the dyes and lakes that are often used in watercolours (Figure 2). Light, particularly UV radiation, can promote chemical degradation such as chain scission of the cellulose in canvas which can potentially cause weakness (and subsequently tears) in the support or changes to the paint binders.

Figure 2: Watercolour painting showing fading due to light exposure.

Air pollutants such as sulphur dioxide, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulphide and ozone will also damage paintings. Acids formed by sulphur dioxide and carbon dioxide in the presence of moisture will damage organic components, hydrogen sulphide can react with lead-based pigments and cause them to blacken and ozone, a powerful oxidiser, may cause fading, loss of tensile strength and accelerated aging.

Dust can cause deterioration by attracting moisture and insects and also by abrading the surface of a painting.

Mould is usually caused by excessive exposure to moisture, either as a result of high relative humidity (> 70 %) or flooding. As moulds feed on the binding medium, sizing in canvas or the paste used in a lining, they are most commonly seen on the reverse side of paintings.

Rodents and insects such as beetle larvae, termites and silverfish can attack the wooden panel supports or the wooden stretchers of canvas paintings. Take action to deter cockroaches and flies (see the chapter Mould and Insect Attack in Collections) as their excrement is disfiguring, can be very difficult to remove from the surface of artworks and because it is acidic, may damage the paint or varnish layers.

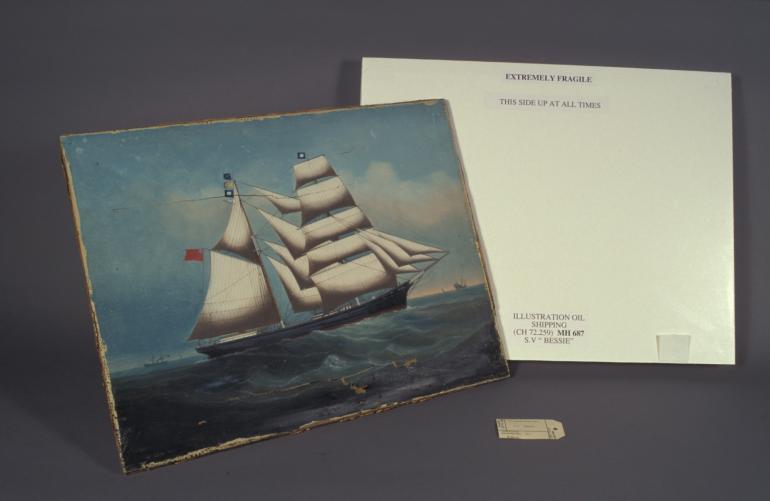

Many paintings on stretched canvas are very susceptible to physical effects such as vibrational forces, shock and impacts. Continual or excessive vibration, particularly during transportation or storage in areas subjected to extreme vibrations, can lead to paint loss. Paintings can also be damaged by poor handling or storage which may lead to tears, chipping, abrasion, loosening or even breakage of frames (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Oil painting damaged by poor handling and storage.

Paintings may also suffer because of the inherent instability of the materials from which they are made. Examples of these additional problems include:

- flaking of ochres as the support material for a bark painting attempts to return to its original shape;

- breakdown and yellowing of natural oil or resin-based varnish layers; and

- changes in colour and material failures as a result of using less stable, non-traditional materials. This is particularly so for paintings produced in the 20th century due to the immense range of synthetic materials that have become available to practising artists.

Poorly selected restoration materials may eventually lead to a visually incohesive artwork as those materials degrade and fade over time.

Preventive Conservation

Environment

Maintain an appropriate, stable environment and control light levels to slow the ageing processes that contribute to the deterioration of paintings. A stable environment is also important to minimise the damage to aged, less flexible canvas and to prevent distortion of wooden backing panels.

Ideally the storage and display environment for paintings should have temperatures and relative humidity levels in the ranges 15 -25 °C and 45 - 55 % respectively with maximum fluctuations of 4 °C and 5 % in any 24 hour period.

Most of the common backing materials, such as canvas, wood, parchment, vellum and even bone and ivory will respond to changes in relative humidity. It is important therefore, when deciding where to hang an artwork, to choose a location that is not prone to large variations in temperature and relative humidity. Do not, for example, hang a painting above a fireplace due to the increased temperatures of the brickwork, the resultant lower relative humidity environment and the possibility of smoke damage. Maintain conditions that will neither encourage embrittlement and desiccation nor too much flexibility and/or mould growth. Methods for controlling relative humidity fluctuations are described elsewhere (see the chapter Preventive Conservation: Agents of Decay).

As watercolours and other paints formed using dyes and lakes are the most sensitive to damage by exposure to light, restrict light levels to 50 lux with a maximum UV level of 30 µW/lumen (1500 µW/m2). Oil, tempera and acrylic paintings can tolerate higher light levels up to 200 lux and 75 µW/lumen (15,000 µW/m2).

Never expose paintings to direct daylight. If windows or skylights are present, use curtains or blinds to eliminate daylight. Cover fluorescent lights with UV filters and install individual switches for each aisle or storage area so that only the minimal quantity of light required for work is used. When the area is not in use, switch off all lights with the exception of emergency lighting. Full details of other light control techniques are available elsewhere (see the chapter Preventive Conservation: Agents of Decay).

Frames and Framing

Frames are both functional and decorative elements. They protect the artwork they surround, provide a means of attaching paintings to the wall and enhance the overall aesthetics of the paintings that they house. Frames original to the painting or selected by the artist are often over-painted, removed or discarded, depending on the current fashion of the day. It is recommended that existing frames on paintings be left ‘as is’ until a significance assessment and condition report have been prepared by a conservator.

For paintings that no longer have frames, framing can provide the correct tension for the canvas, enhance exhibition potential, make storage and handling easier and buffer against changes in ambient conditions. A backboard, for example, minimises relative humidity changes for the support and may help to prevent paint from flaking. Although paintings are generally not glazed as it can detract from the artists’ intent, it serves to protect valuable and fragile paintings by buffering against changes in ambient conditions and by preventing the ingress of dust, dirt and insect excrement.

Commonly used glazing materials include glass and acrylic materials such as Perspex™. Although chemically safe, glass is heavy and can shatter and damage a framed work, whereas acrylics are lighter and shatter-resistant. A further advantage of acrylic glazing is the opportunity to use acrylics that filter UV light. Do not allow direct contact between the painted surface and the glazing as this will increase the risk of mould growth and the abrasion of pigments.

The framing and rehousing of paintings has become a specialised field within conservation (‘conservation framing’) with different materials and methods used from those of typical commercial framing operations. Some differences include the:

- use of archival materials;

- use of a backing board to protect the painting from physical damage, dust and changes in environmental conditions;

- fixing of attachment brackets only to the frame and not to the back of the painting;

- use of padding or a spacer in the gap between the painting and frame to provide a buffer;

- use of UV-filtering acrylic glazing; and

- avoidance of direct contact between the glazing and the surface of the painting.

Before proceeding with framing, make sure that you have checked the following points with the framer:

- the depth of the frame, ensuring that there is room for a spacer and for the painting to be safely positioned;

- the method by which the painting is to be fixed within the frame;

- the types of framing materials that will be used; and

- the types of backing boards and glazing materials used for the painting.

To provide additional environmental protection for particularly valuable paintings, conditioned silica gel or Artsorb® sheets can be incorporated into the frame. Do not attempt this type of treatment without professional advice however as there are risks if correct procedures and conditioning of the silica gel are not carried out.

Handling

Avoid contact with the painted surface and the back of the canvas when handling paintings. This will reduce the chance of leaving fingerprints on varnishes or of dislodging fragile surfaces. Although wearing white cotton gloves is generally recommended when handling paintings, powder-free latex or nitrile gloves are equally acceptable, especially where cotton fibres may catch on uneven surfaces or be deposited on soft paint layers. Take care when handling works displaying impasto techniques or similar artworks, as there is the possibility of the gloves catching on the protruding paint. Other handling recommendations include:

- plan all handling activities carefully. If moving a painting for instance, clear all obstacles from the proposed route and make all necessary preparations for the safe, final placement of the painting;

- clean hands, roll up sleeves and remove jewellery to reduce the risk of damaging the paint surface;

- hold unframed canvases or panels only at the edges;

- handle framed paintings at the sturdiest part of the frame and not the decorative ornamentation. Never hold frames by the top as this weakens the frame which may break apart if the mitres are already weak;

- inspect paintings and frames carefully before moving them as some older, ornate frames may have sections that are loose;

- as long as the frame is in good condition, carry the framed painting with one hand underneath the bottom of the frame and the other on the side, ensuring that the image side of the painting is facing inwards towards your body;

- if the frame is in poor condition, place it on a support and carry the support;

- if the painting is large, ensure that there are at least three people available to move the painting, one on each end and the other to look out for obstacles and to warn pedestrians;

- have padded blocks available so that the painting can be rested off the floor if necessary; and

- if possible, consider transporting large paintings on padded trolleys. Secure the paintings well before moving to a new location.

To reduce vibration and shock from movement, transport paintings in protective crates with foam padding and use a professional art handling and transportation company where necessary. When particularly valuable objects are moved by commercial transport companies, include vibration and shock data loggers with the paintings to monitor handling practices. These loggers will record the date and time of any physical shock or excessive vibration to which the painting may have been subjected while in transit or storage.

Storage and Display

Before hanging a painting for display, check the frame and hanging system to ensure they are in good order, are sufficient for the weight of the painting and are arranged so the weight is evenly distributed. If there is no hanging system in place, do not simply hammer in nails or use string or cord to hang paintings. Take the painting to a conservation framer for advice on the most appropriate hanging method.

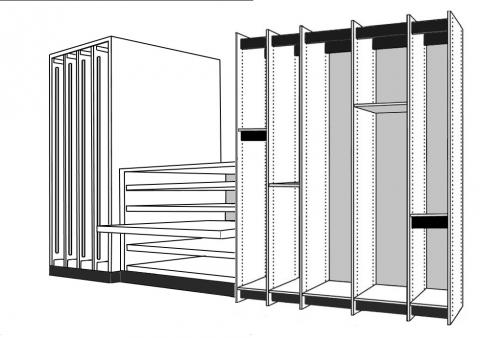

A storage space for paintings should be flexible and take into account the nature of the collection, potential collection growth and changes in exhibition and storage policies. There are many different options ranging from metal bins and storage units to wire mesh moving screens.

Hanging storage using wire mesh moving screens is a good way to store paintings (Figure 4). Wire mesh screens, usually composed of a rigid wire mesh supported on a metal or wooden frame, provide an economic use of floor space and paintings can be easily located and examined in situ. Paintings can be hung (using an appropriate hanging system) on both sides of the screens. These are attached to an overhead and floor track that allow them to be moved manually. Two or more people are normally required to remove paintings from these racking systems.

Figure 4: Wire mesh screen used to store paintings.

Follow the guidelines below if considering the use of wire mesh moving screens to store paintings:

- ensure that the painting is equipped for hanging and is in good condition. Consult a professional framer if it does not have a frame or other form of hanging system;

- consider attaching a backing board to a painting to protect the verso (back) of the painting from damage;

- test the strength of the hanging system and the hooks in the racking before hanging;

- hang heavier paintings lower than lighter paintings;

- check that frames will not damage adjacent frames;

- do not hang paintings in high traffic areas or narrow spaces where they may be accidentally damaged;

- remove or replace wire and hanging hardware that protrudes too far from the back of a painting; and

- do not use vertical storage for paintings that are in poor condition, are fragile or have flaking paint.

If framed images are not hung, store them according to the following guidelines:

- stand paintings upright and in the right orientation;

- place sheets of acid-free board or Fome-cor®, larger than the paintings, between each frame;

- place padding, such as Fome-cor ®, underneath the stack to protect the edges of the frames;

- raise the stack from the floor by using ethafoam blocks, over skidproof mats, or place a wedge against the outermost frame to prevent slippage;

- stack framed works, alternating face-to-face and back-to-back. This prevents the fittings on the back of the frame from scratching the front. Where possible, use pieces of board or other suitable material in between each frame;

- when stacking uneven sized framed works, ‘bridge’ the works so that the frames rest on each other and do not make contact with the painting itself; and

- do not lean or stack paintings against exterior walls.

A custom wooden storage unit consisting of a number of bins can be made to accommodate two to three paintings in each section (Figure 5). Seal all wood (exterior grade plywood), preferably with two to three coats of a water-based polyurethane sealer to reduce off-gassing from the wood. Exterior walls should be at least one inch thick with separating dividers placed in grooves at the top and bottom. Raise the base of the unit so that it is at least 15 cm off the ground and pad the bottom of each section with ethafoam. Place units against an interior wall for added structural and environmental stability. If there is more than one painting in a bin slot, separate each one with some board or other appropriate material.

Figure 5: Custom wooden storage unit comprising individual bins for paintings.

Protect unframed paintings, fragile paintings or those with flaking paint by storing them in custom-made boxes. Construct these boxes from archival materials and store them horizontally in enamelled metal cupboards, map drawers or shelves.

Inspect and monitor paintings regularly, particularly if they are in storage.

Do not use inks or sticky labels on the backs of paintings as they may eventually bleed through to the front or cause puckering to the front of the work. Chemical residues from the adhesive on the labels may also migrate to the front of the work. Catastrophic damage can also be caused by spilling inks or other liquids.

Do not use aerosols and spray cleaners near exposed paintings, as the solvent propellants have the potential to cause softening and damage to paint surfaces.

Treatments

Documentation

Carefully document the history and condition of any artwork as soon as it enters a collection. Record details concerning the painting and the frame, including:

- notes about the artist, the date of the painting, dimensions (framed and unframed) and the title of the work;

- photographs including overall shots of both sides and any detailed images taken from various angles to highlight special features such as labels, damage or other interesting features; and

- a condition report recording the dimensions, materials used in the painting and supports, details of any previous restorations or irregularities, descriptions of the type and condition of all materials present (even if unsure of their nature) and labels or writing on the edges or back.

Evidence of an underlying work may require specialist examination using infra-red, UV or X-ray photography.

Cleaning and Repairing

Conservation treatment of paintings is a specialised area of work, requiring high levels of skill and training. As inappropriate treatments have the potential to damage and compromise the integrity and value of a painting, any decision to treat a painting must be made only after consulting conservation and curatorial professionals.

Each painting is unique and no general guidelines can be set as to the extent of treatment required. Bearing the above cautionary notes in mind very brief details are given below of the type of work that would require the services of a conservator. These include:

- removing dirt and stains from the surface;

- removing yellowed varnish using solvents to reveal the original colours of a painting;

- consolidating friable and powdery pigments or grounds;

- reattaching loose or flaking paint or relaxing blind cleavage of paints;

- repairing tears or holes;

- lining or re-lining a weakened canvas or strip lining to support a weak tacking edge;

- re-stretching a canvas. Great care is needed to prevent splitting as aged canvas loses its flexibility; and

- re-integration. This involves filling and in-painting the losses of paint so that visual continuity is achieved.

It is important that all conservation work is reversible as conservation materials will also deteriorate over time. Thus, when a recently applied varnish eventually ages and deteriorates, it will be able to be removed. Similarly, materials used in retouching may age at a different rate to the original and may have to be removed at some time in the future.

An example of a painting that required treatment is described below (Figure 6). While not an example of the treatment of an easel painting, the decision making process when planning a conservation treatment remains the same. The painting, a modern Aboriginal bark painting in an acrylic medium, was in the process of being given a collection number when ink was accidentally splashed onto it.

Figure 6: Acrylic painting showing damage from careless handling of ink.

The proposed treatment of this work of art was to:

- assess the damage to the painting and prepare a condition report;

- photograph the painting, including close-ups of damaged areas;

- sketch stained areas to highlight those damaged areas which may not show up sufficiently in a photograph;

- determine the chemical nature of the ink;

- search the literature for all known solvents or reagents which will dissolve the ink;

- conduct spot testing to determine if the chosen reagent will remove the ink without damaging the underlying image; and

- remove the ink area by area.

Should ink removal techniques be likely to affect the underlying paint layers, an alternative to removing the ink may be to over-paint.

All conservation treatments must be fully documented and reversible.

Summary

- Document all aspects of a painting, including details of the artist, title of the work, photographs, sketches and condition report.

- Maintain temperatures and relative humidity levels in the ranges 15 -25 °C and 45 - 55 % respectively with maximum fluctuations of 4 °C and 5 % in any 24 hour period.

- Restrict light levels to 50 lux and UV levels of 30 µW/lumen (1500 µW/m2) for watercolours and paintings based on dyes and lakes. Maintain light levels at 200 lux and UV levels at 75 µW/lumen (15,000 µW/m2) for oil, tempera and acrylic paintings.

- Do not touch front or back surfaces with bare hands.

- Be extremely careful when handling paintings, use appropriate systems for hanging them and obtain conservation framing advice for large and heavy works.

Bibliography

Bomford, D., 1984, Conservation and Storage: Easel Paintings, in Thompson, J. M. A (Ed.), Manual of Curatorship: A Guide to Museum Practice, London, Butterworths, Second edition.

Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI-ICC Notes. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Conservation Institute.

10/3, 1993, Storage and Display Guidelines for Paintings.

10/4, 1993, Environmental and Display Guidelines for Paintings.

10/10, 1993, Backing Boards for Paintings on Canvas.

10/13, 1993, Basic Handling of Paintings.

Gettens, R.J. and Stout, G. L., 1966, Painting Materials, Dover Publications Inc., New York.

Keck, Caroline K., 1965, A Handbook on the Care of Paintings. Nashville, Tenn., American Association for State and Local History.

Leisher, W.R., 1992, Paintings, in Caring for Your Collections, National Committee to Save America’s Cultural Collections, Arthur W. Schultz (Chairman), Harry N. Abrams Inc., New York, pp.30-39.

Mayer, R., 1991, The Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Techniques, Fifth Edition, Revised and Updated, Viking Penguin, USA.

Moser, K. S., 1992, Painting Storage: A Basic Guideline, in Bachmann, K. (Ed.), Conservation Concerns: A Guide for Collectors and Curators, Cooper-Hewitt, National Museum of Design, Smithsonian Institute, New York and Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London, pp. 57-61.

Simpson, M.T. and Huntley, M., (Eds), 1992, Caring for Antiques, Conran Octopus, London.

von Nostitz, C., 1992, When Is It Time to Call a Paintings Conservator?, in Bachmann, K. (Ed.), Conservation Concerns: A Guide for Collectors and Curators, Cooper-Hewitt, National Museum of Design, Smithsonian Institute, New York and Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London, pp. 63-67.