Organic Materials

Wood

Identification

In some cases, as in the recovery of a blackened object from an anaerobic site, it is not always easy to identify the material type from which the object was made. The appearance of an object and its probable usual use, along with the fibrous nature of wood usually allow wooden objects to be identified.

Consult timber specialists if it is important to identify the wood species from which an object has been made. By examining either a polished end-grain surface or by preparing a microscope slide of the end-grain, the identity of a wood sample can usually be determined. Take samples from the least obtrusive part of the object to minimise damage to the object. Identification is relatively straight forward if the sample’s cell structure is in good condition and the wood is not heavily stained or blackened.

Handling

Ascertain the condition of wet wood before handling it as its appearance can be deceptive. The condition of recovered wet wood can vary from solid to mushy. Handle it accordingly, especially as the surface is usually soft. Use a very thin needle to determine the ‘softness’ of the surface and interior of the object. Test the softness in a number of places so that the overall condition of the wood can be determined. Being bulked by water, a wooden object can appear quite robust when in reality it is highly degraded and in need of support before it is moved.

Follow the general guidelines described in the Introduction to this chapter (On-site storage considerations) for wooden artefacts.

Initial Stabilisation

To stabilise wood recovered from wet sites:

- keep objects wet;

- maintain the support provided by water for smaller fragile wooden objects recovered from underwater sites and raise them in a suitable container, preferably sealed with a lid;

- store objects at low temperatures and in the dark if possible;

- change the water if biological growth is observed;

- use freshwater with a fungicide if biological growths are persistent and storage is prolonged (sample wood before adding biocides if a subsequent dating determination is planned); and

- store metal-contaminated wooden objects separately from non-contaminated objects.

Wet wood must be kept wet once recovered. Irreversible damage will occur if it is allowed to dry before treatment (see Figure 1). Use baths, plastic bags or containers, tubs or even wet cloths covered with plastic to keep artefacts wet.

Initially store wooden objects in water from their recovery sites. If sufficient freshwater is available then use it for objects excavated from a marine environment so that desalination can begin. Incorporate a fungicide such as Kathon (0.1 – 2 %) in the solution if biological growth cannot be controlled by changing water, refrigeration or other means of low temperature storage.

Leather

Identification

The ease of identifying leather is directly related to its condition. Highly degraded wet leather may appear as nothing more than mush or just as a mass of fibres held together by corrosion products. Often however, wet leather retains its shape and its characteristic appearance, making its identification relatively easy.

If an object is thought to be leather but there is some doubt, confirm its composition by infra-red spectroscopic analysis. This is a specialised technique which only needs a pin-head sized sample for the analysis.

Handling

When handling leather objects:

- use supports; and

- wrap in gauze or similar material and sew the edges together.

Handle thin or fragile leather extremely carefully as it is prone to tearing while wet. The best method for handling is to insert a support beneath the leather in its storage solution and to ‘float’ the leather onto the flat surface. Use the support, not the leather, when lifting the object.

Wrap small leather objects in soft gauze (e.g. tulle) and sew the edges together to make handling easier and to ensure that all parts of the object will be retained.

Initial Stabilisation

To stabilise leather from a wet site:

- store wet;

- store at low temperatures and in the dark if possible;

- change the water if biological growth is observed;

- store in freshwater containing an appropriate fungicide if biological growths persist; and

- store metal-contaminated leather objects separately from uncontaminated objects;

Do not allow wet leather to dry out before it is treated. For marine objects, seawater is acceptable for short-term storage before transferring them to a freshwater solution. If a fungicide is needed, only use pH neutral or slightly acidic fungicides such as Densil ‘P’ as alkaline fungicides contribute to leather breakdown. If possible store wet leather in a refrigerator or similarly cool environment. Do not store wet leather for long periods as deterioration processes continue.

Bone, Ivory and Horn

Identification

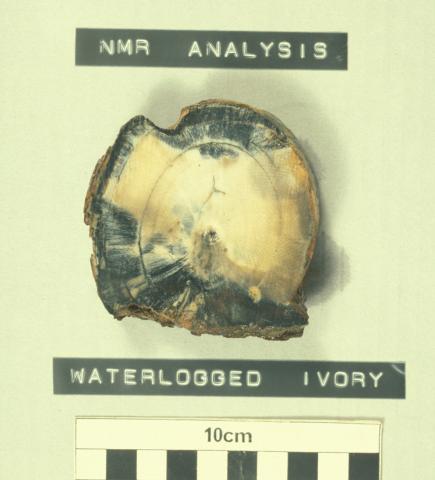

Identifying bone and related materials is often complicated by their dark colouration (due to burial in predominantly anaerobic conditions) or staining by corrosion products. As a consequence, these materials have been mistaken for materials such as wood and ceramics. If bone and ivory objects are incorrectly identified, they may be treated inappropriately. Use microscopic examination to distinguish these materials (Penniman 1952).

If microscopic identification is inconclusive, use infra-red (IR) spectroscopic analysis. IR analysis will allow bone and ivory to be clearly distinguished from other material types. The IR spectra of bone and ivory are similar however, particularly if samples are degraded.

Handling

Bone, ivory and horn objects are often fragile and require careful handling.

If these objects have been closely associated with iron objects they are often heavily contaminated with iron corrosion products. These often create a hardened exterior surface which can hide a multitude of problems, including a highly degraded core (Figure 4). Take care not to dislodge these protective outer layers as they can be quite brittle. Wrap ivory and bone objects in bubble wrap or similar materials for protection.

Figure 4: (a) Tusk fragment from the Vergulde Draeck (1656) shipwreck showing contamination with iron corrosion products.

(b) Cross-section of the same fragment showing different areas of deterioration in the inner parts of the tusk.

Initial Stabilisation

To stabilise bone, ivory or horn materials recovered from wet sites:

- store wet;

- use water from the excavation environment or freshwater;

- store at low, but not freezing temperatures if possible; and

- store metal-contaminated objects separately from uncontaminated objects.

Ensure these objects remain wet as the laminated structures of ivory and horn are usually coherent while wet but tend to delaminate upon drying. Short-term storage in the water from which the objects were recovered is acceptable.

After initial storage, place the items in freshwater at low temperatures (about 5 °C) to begin desalination, thus avoiding the need to incorporate a fungicide. This is important as the complex nature of these material types (inorganic and organic components with different pH tolerances) means that the choice of an appropriate fungicide is very difficult.

Textiles

Textiles include materials made up of cellulosic fibres such as cotton, flax, hemp, jute and sisal, and proteinaceous fibres such as wool and silk. Fabrics, rope and matting have all been recovered from wet sites. Usually textile materials will survive in a wet environment only if the site is anaerobic or if they have been protected from their surroundings by encapsulating concretions.

Identification

Identifying fibres usually requires a high power, good quality microscope and access to appropriate references which highlight the features of different fibre types. As textile fibres from wet sites are usually highly degraded, choose the best fibres for examination to ensure that characteristic features are still evident.

Handling

When handling wet textiles:

- support them so they do not carry their own weight;

- use flat supports for flattened textiles; and

- use sewn netting for three-dimensional objects.

Of the organic materials wet textiles are often the most difficult to handle because of their fragility and inability to maintain their own shape when removed from their aqueous environment. At all stages of treatment most textiles need some sort of support to maintain their structural integrity.

Support flat textiles on a glass plate or similar, separated from the support by interleaving with synthetic papers or screening material.

Three-dimensional textiles like rope usually need to have a support sewn around them to maintain the overall integrity of the object and to prevent fibre separation and loss. Gauze screening, tulle for example, is preferred as it allows relatively easy access for cleaning and offers little resistance to both the outward diffusion of dirt, salts and corrosion products and to the inward movement of consolidants and other treatment chemicals.

Initial Stabilisation

To stabilise wet textiles:

- store wet, using either the water from which the textile was recovered or freshwater;

- support and wrap fibrous textiles while in the wet state;

- store at low temperatures and in the dark if possible; and

- consult a conservator for advice on incorporating appropriate biocides if longer term storage is likely.