Photographic Processes

Knowledge of photographic processes and their features is important in order to identify photographs. This knowledge allows those responsible for their care and preservation to:

- determine the most appropriate environmental conditions and storage requirements for particular photographs;

- differentiate between originals and copies; and

- separate cellulose nitrates and acetates from other photographic materials to minimise damage to entire collections.

Daguerreotype (1839 - 1860s)

Direct Positive

The process of producing a daguerrotype involved the following:

- a thin silver sheet was sweated onto a copper plate and then highly polished;

- after sensitising with iodine vapour the plate was exposed in the camera; and

- the latent image was then developed using mercury fumes.

Because the image was easily damaged daguerreotypes were housed behind glass with attractive brass mounts and leather-covered cases. Plastic cases, known as union cases, were introduced in 1854. These cases were made by heating and pressing a mixture of gum shellac and sawdust (or other fibrous material) into moulds, making this the first commercial example of a thermosetting plastic.

Daguerreotypes are recognised by their silver surface, sometimes being called the ‘mirror with a memory’.

Calotype (1840 - 1860s)

In its strictest sense the term calotype refers to the negative produced when a silver-sensitised sheet of paper is exposed in a camera. The positive prints produced from this negative, often called calotype prints or salted prints, lacked detail due to the paper fibres which produced a fuzzy appearance.

Salted Prints (1840 - 1860s)

Salted prints have the following features:

- good quality paper was coated with light-sensitive silver salts and printed out in sunlight to produce the image; and

- prints from glass negatives gave a sharper image than those from a paper negative.

Although the image was initially fixed using a strong salt solution, sodium thiosulphate (hypo) was used after 1841. The hypo dissolved out unexposed silver chloride producing a brighter image.

Ambrotype (1851 - 1870s)

Direct Positive

An offshoot of the wet collodion process, the ambrotype is an underexposed negative with a black backing. This backing gives it a positive appearance. Ambrotypes were packaged the same way as daguerreotypes, behind glass within a gilded, leather-embossed case.

Tintype (1852 - 1940s)

Direct Positive

Similar to the ambrotype, the tintype is in fact a sheet of japanned iron, coated with a sensitised collodion emulsion. Exposed in the camera and then immediately developed, the tintype exhibits a dull positive image with creamy highlights.

Although sometimes mounted in the same manner as ambrotypes and daguerreotypes tintypes were more commonly mounted in cards or albums. They are found in a range of sizes right down to buttonhole size. Abraham Lincoln’s presidential election campaign used his image on a tintype badge.

Wet Plate Process (1851 - 1880s)

Collodion Negative

Features of the wet plate process include the following:

- a glass sheet coated with collodion and sensitised with potassium iodide and silver nitrate was exposed in the camera while still wet;

- developed immediately after exposure the resulting negative produced fine detail;

- if allowed to dry before exposure a lot of sensitivity is lost; and

- the wet plate is identifiable by its creamy-grey appearance.

Most commonly used in conjunction with albumen paper to produce prints, it was very popular until the introduction of the gelatin dry plate in 1880. The fumes from preparing and exposing the wet plate affected photographers’ health.

Albumen Print (1850 - 1920s)

The albumen print:

- is coated with light sensitive silver salts and egg white solution;

- was normally produced by contact printing in daylight from a wet plate negative; and

- the image has yellow highlights with reddish-brown higher density areas.

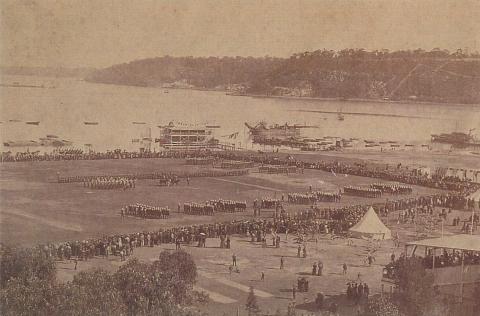

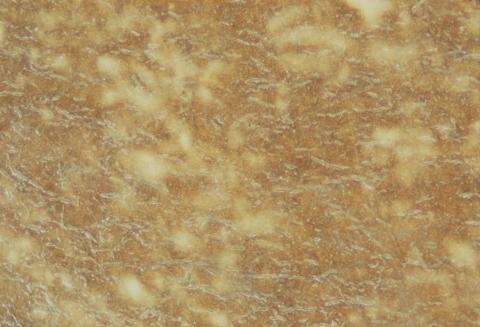

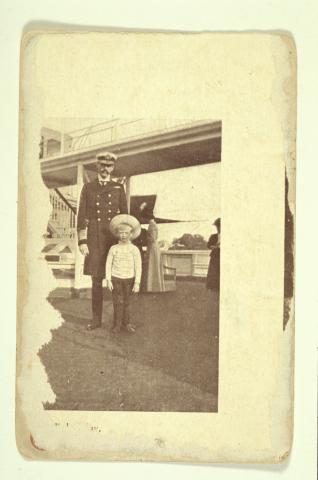

The albumen print (Figure 2) is the photograph most often found before the turn of the century. Most visiting cards are albumen prints. Although it was still used until the 1920s, the albumen process effectively went into decline after 1880.

Figure 2: (a) Albumen print of the Swan River, Perth, Western Australia c 1897.

(b) Close-up of the surface showing paper fibres below the emulsion.

Gelatin Dry Plate Negative (1880 - Present)

In the 1870s Dr Leach Maddox developed the gelatin emulsion, which is the basis of modern photography. The gelatin plate needed no sensitising by the user and it came packaged ready to be exposed. This ease of use meant it quickly supplanted the wet plate method and glass plates. It was in common usage until recent times.

Gelatin Paper Prints (1880 - Present)

The advances made during the 1870s with gelatin emulsion resulted in the preparation of a gelatin bromide developing out paper. Developing out paper uses a chemical solution to produce a black and white image which is developed using artificial light in a darkroom.

It was not popular with photographers who were geared to printing out paper and the warm tones they produced. Printing out papers are contact printed using daylight and the particle size of the silver in these images is very small. This tends to scatter the light that hits them, giving the image its characteristic warm tone. Once the image density was satisfactory it was then fixed. The silver in developing out paper is larger than in printing out paper and produces an image that exhibits a neutral hue.

The introduction of a baryta layer (barium sulphate mixed with gelatin) below the gelatin layer added brilliance to the print. Gelatin printing out paper rapidly replaced both albumen and collodion printing out paper as the preferred print material. Improved sensitivity and speed in papers in the early 1900s increased demand for developing out papers and by 1920 printing out paper was rarely used.

Platinum Prints (1880 - 1920s)

Platinum prints:

- were admired for their tonal range and soft image;

- did not fade; and

- were usually steel-grey in colour but prints could be produced with a brown tone.

As platinum became increasingly expensive in the early 1900s, imitations were manufactured using silver-gelatin and also collodion. As the paper fibres of the platinum print are discernible under low magnification microscopic examination, it is easy to differentiate an original from a copy.

Collodion Prints (1880 - 1920)

Collodion prints exhibited the following characteristics:

- the same high gloss and reddish-brown tones as gelatin printing out paper;

- could be manufactured with a matt finish to imitate platinum prints. With gold and then platinum toning the image is very stable and this, coupled with its resistance to moisture, means that these prints have resisted fading extremely well; and

- are easily distinguished from platinum prints as they have a baryta layer below the emulsion. The paper fibres are not visible under microscopic examination.

Cyanotypes (1880 – 1920)

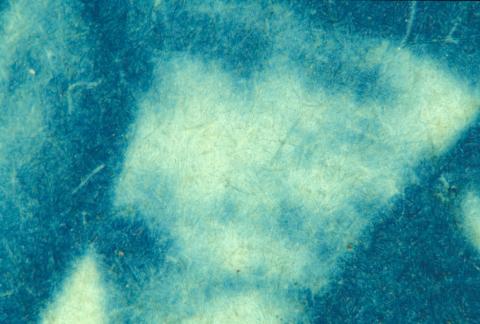

Originally developed in the 1840s this process was soon forgotten, only to reappear some 40 years later. Its bright blue appearance meant it never really gained widespread popularity and its main claim to fame was its use in the reproduction of engineers’ drawings. From this came the term ‘blueprint’ (Figure 3).

Figure 3: (a) Cyanotype c 1890.

(b) Close-up of the surface showing the image within the paper fibres.

Celluloid (Cellulose Nitrate) (1889 - 1950)

A refinement of Alexander Parkes’ 1861 invention, cellulose nitrate film was coated with a silver gelatin emulsion. Available in both sheet and roll format, eventually it was to dominate as the preferred negative material.

Using roll film in a suitably controlled camera, it was possible to expose a number of negatives rapidly. The smaller size of these negatives necessitated the use of developing out paper material, signalling the end of the glass plate and the printing out paper method of photography.

Cellulose Acetate (1930 - 1960s)

The inherent instability and flammability of cellulose nitrate resulted in the production of cellulose acetate ‘safety film’. This was in turn superseded by cellulose triacetate film (1950) which in turn was overtaken by polyester (1965).

Photomechanical Processes

Photomechanical prints include:

- collotype (1870 on);

- photogravure (1880 on); and

- letterpress half-tone (1885 on, Figure 4).

They are not true photographs as they have no emulsion and are printed by machine. Low magnification shows up the printed pattern.

Figure 4: (a) Postcard – letterpress half-tone.

(b) Detail of the child’s face showing the dot pattern.

Pigment Prints

Using inorganic pigments and the reaction of bichromates to render gelatin or gum arabic insoluble, these prints do not fade. Although a large range of pigments could be used, the colours chosen were normally warm chocolate browns.

Examples of pigment prints include:

- carbon print (1860 - 1930s);

- gum bichromate (1890 - 1930s); and

- woodburytype (1865 - 1890s).

The woodburytype was an early photomechanical process that used pigmented gelatin to produce the image.

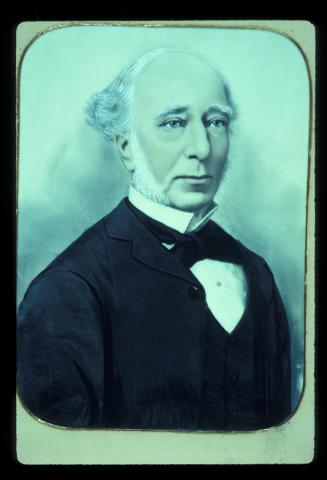

Opaltypes (1880 – 1920)

Opaltypes (Figure 5) are characterised by:

- a positive image on milky white glass;

- many are hand tinted or retouched; and

- the image layer can be either carbon, silver-gelatin or platinum.

Figure 5: Opaltype – hand-tinted image on opal glass c 1890.

Lantern Slides (1851 - 1900)

Lantern slides can be identified by the following:

- the emulsion layer can be either collodion, albumen, carbon pigment or silver-gelatin;

- these were often tinted or hand painted; and

- the slide was usually formed by sandwiching two sheets of glass together to protect the image.

Stereograph (1851 - 1920)

Although there are examples of stereoscopic daguerreotypes and calotypes, the vast majority of these images are in the form of albumen prints. Silver-gelatin and collodion prints were also produced in stereographic pairs.

Photo-ceramic (Photo Enamel) (1950s - Present)

The photo-ceramic process involves:

- using pigments in a variety of ways to produce an image on porcelain or metal;

- the image is sealed by glazing; and

- the images do not fade.

Colour (1860s - Present)

Hand-colouring of images began at the inception of photography. There are many fine examples of early hand-tinted daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, prints and emulsions of all sorts. Before 1900 all colour photography involved either hand-tinting, pigment prints or photomechanical processes. In 1904 the Lumière brothers invented the autochrome process, an additive process, but it was not until 1935 that the modern era of colour photography started with the introduction of Kodachrome films.

A few of the major developments of colour processes are listed below.

- carbon print (1860s - 1930s);

- gum bichromate (1890s - 1930s);

- collotype-photomechanical (1868 - present);

- autochrome-additive process (1904 - 1940s);

- modern colour photography (1935 - present);

- instant colour process (1963 – present, Polaroid); and

- digital output photography - electrostatic, ink jet and dye sublimation prints (1985 – present)

A tabular summary and guide to the identification of the various photographic processes is provided in Appendix 7.